One consideration of this essay is that it is best if the reader has some familiarity of the music of Suzanne Vega and has read McCullers’ novel. Understanding that those conditions are not always met, I’ve tried to write this piece in a way that could hold the interest of people unfamiliar with either artist. A side benefit is that it might nudge someone to pick-up the novel and to explore Vega’s music.

A second consideration is that the associations between Carson McCullers’ novel and Suzanne Vega’s music are subjective to my personal experience with the material; it is therefore not an “analysis” of the works but merely one person’s impressions.

Decades and geography separate the lives and work of these two artists; McCullers published The Heart is a Lonely Hunter in 1940 and died in 1967. Vega has publicly spoken of her admiration for McCullers’ work but I do not make the claim that her work was directly inspired by McCullers. Perhaps some of it was; perhaps some is coincidence. Rather, this essay is about how for this reader and listener, the act of reading McCullers conjures up the music of Suzanne Vega and how, when listening to Vega’s music, a distant reflection of McCullers’ images and characters often materializes.

Mick Kelly

There are several prominent characters in The Heart is a Lonely Hunter; one is Mick Kelly who we first meet entering the New York Café:

Biff sensed that someone was standing in the entrance and he raised his eyes quickly. A gangling, towheaded youngster, a girl of about twelve, stood looking in the doorway. She was dressed in khaki shorts, a blue shirt, and tennis shoes – so that at first glance she was like a very young boy. Biff pushed aside the paper when he saw her, and smiled when she came up to him.

An important association of Suzanne’s music with this novel is captured in this paragraph. Although we are in the southern U.S. just before WW II, into the aptly named “New York Café” (faint echo of Vega’s hometown; faint foreshadow of “Tom’s Diner”) walks Suzanne Vega/Mick Kelly. Of course, because Mick is entirely a phantom in our imaginations as conjured-up by McCullers there is no way to make a case for the similarity of Vega at twelve to Mick Kelly, but nevertheless it is Suzanne that enters my version of McCullers’ New York Café.

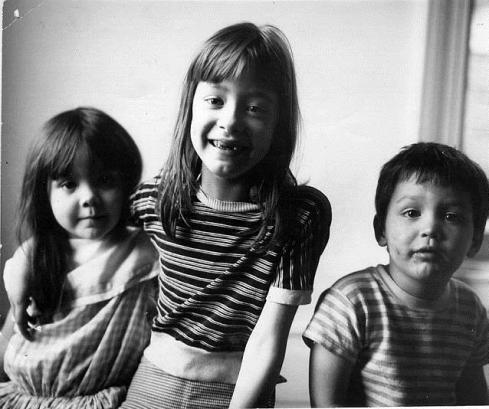

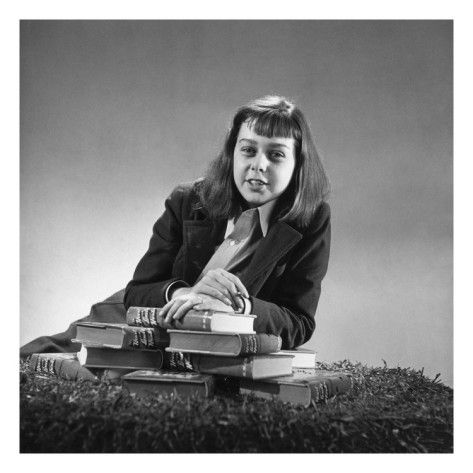

It is startling to see photos of McCullers as a young woman – they are eerily like those of Suzanne –geometries of straight hair and bangs; their pale-skinned angularity. Whether or not Mick is modeled on McCullers I cannot say but in my imagination it is Carson/Mick/Suzanne who we follow through the novel.

The slightly androgynous quality of Mick Kelly is something Suzanne seems to have also possessed growing up and in her early years as a performer. Similar too is the role Suzanne/Mick pays in taking care of her younger siblings (Vega, in an interview: “After we moved out of East Harlem when I was a bit older, I would take care of my brothers and sister for hours”). Of Mick, McCullers wrote:

Finally she went back in the kitchen and took Ralph out of his highchair and put a clean dress on him and wiped off his face. Then when Bubber got home from Sunday School she was ready to take the kids out. She let Bubber ride in the wagon with Ralph because he was barefooted and the hot sidewalk burned his feet. She pulled the wagon for about eight blocks until they came to the big, new house that was being built. The ladder was still propped against the edge of the roof, and she screwed up nerve and began to climb.

‘You mind Ralph,’ she called back to Bubber. ‘Mind the gnats don’t sit on his eyelids.’

Significantly Mick lives, as do most of the other characters in the novel, a largely secret interior life-of-the-imagination. Music and the dream of composing music and conducting an orchestra with her name in lights animate Mick’s existence. Because she and her family lack the resources to purchase records or instruments, her engagement with music is predominately in her head, reinforcing the novel’s tone of inward-looking isolation and alienation. A set-piece is Mick hearing Beethoven’s Third Symphony on a neighborhood radio:

In the quiet, secret night she was by herself again. It was not late – yellow squares of light showed in the windows of the houses along the streets. She walked slow, with her hands in her pockets and her head to one side. For a long time she walked without noticing the direction…She looked around and saw she was near this house where she had gone so many times in the summer. Her feet had just taken her here without her knowing…

The radio was on as usual. For a second she stood by the window and watched the people inside. The bald-headed man and the gray-haired lady were playing cards at a table. Mick sat on the ground. This was a very fine and secret place…

After a while a new announcer started talking. He mentioned Beethoven. She had read in the library about that musician – his name was pronounced with an a and spelled with a double e…The announcer said they were going to play his Third symphony. She only halfway listened because she wanted to walk some more and she didn’t care much what they played. Then the music started. Mick raised her head and her fist went up to her throat…

This was her, Mick Kelly, walking in the daytime and by herself at night. In the hot sun and in the dark with all the plans and feelings. This music was her – the real plain her.

Mick harbours a powerful desire to escape the limitations of her circumstances. She will “be a great world-famous composer” and will “stand up on the platform in front of the big crowds of people.” “The curtains of the stage would be red velvet and M.K. would be printed on them in gold.” “It would be in New York City or else in a foreign country.”

When she was 15 Suzanne wrote “First Day Out.” In it we see the inner fantasy life and solitude that also animates Mick and is a thread through Vega’s work:

Here I am, all by myself, and I’ll admit I’m scared

All I’ve got is my guitar and a couple of dollars to spare

And I know even that’s not gonna last me long.

I suppose I could pick myself up and carry myself back

home

But after what I put my folks through, I think I better

stay alone.

Anyhow, five years of aching are packed behind this

plan

Since I was ten, I’ve wanted to get out of the city and

live out on the land.

Suzanne’s song “As a Child” (from the album 99.9 F Degrees) is one of several that emphasize the way that Vega, like McCullers, incorporates the life-of-the-mind into their art:

As a child / You have a doll / You see this doll

Sitting in her chair

You watch her face / Her knees apart / Her eyes of glass

In a secretive stare

She seems to

She seems to

Have a life

Pick up a stick / Dig up a crack / Dirt in the street

Becomes a town

All of the people / Depend on you / Not to hurt them

Or bang the stick down

One can picture Mick amusing herself or Bubber and Ralph with a stick on the sidewalk outside their home.

Alienation, Struggle, Stoicism

The people in The Heart is a Lonely Hunter exist in isolation and silence from each other; when they do try to connect it is with and through a deaf-mute (“John Singer”), who they each imagine is the one who understands their struggles and yet he often barely registers their flutter of mouths forming shapes and who writes, in his own isolation, to a far-off friend who cannot read:

They are all very busy people. In fact they are so busy that it will be hard for you to picture them. I do not mean that they work at their jobs all day and night but that they have much business in their minds always that does not let them rest. They come up to my room and talk to me until I do not understand how a person can open and shut his or her mouth so much without being weary.

A café owner is left to wonder

Who would he be loving now? No one person. Anybody decent who came in and out of the street to sit for an hour and have a drink. But no one person. He had known his loves and they were over. Alice, Madeline, and Gyp. Finished. Leaving him either better or worse. Which? However you looked at it.

A doctor sits “in his dark kitchen alone” reading a book by a round-bellied wood stove in solitude for hours.

In her song “Wooden Horse,” Vega writes about the tale of one “Kaspar Hauser” who, the legend goes, lived in isolation for years as a child in the area in or near Nuremberg Germany in the 1820’s. He was found wandering the town and taken in by authorities. Whatever the truth of his existence, he was and is an image of solitary existence — without contact, conversation, or light — his only possessions a small wooden toy horse:

I came out of the darkness

Holding one thing

A small white wooden horse

I’d been holding inside

And when I’m dead

If you could tell them this

That what was wood became alive

What was wood became alive

In “Rusted Pipe” (from days of open Hand) Suzanne’s protagonist is unable to speak:

Now the time has come to speak

I was not able

And water through a rusted pipe

Could make the sense that I do

Gurgle, mutter

Hiss, stutter

Moan the words like water

Rush and foam and choke

Having waited

This long of a winter

I fear I only

Croak and sigh

In the novel, the doctor…

After the solitary hours spent sitting in the dark kitchen it happened that he began swaying slowly from side to side and from his throat came a sound like a kind of singing moan.

McCullers’ characters do not communicate with each other in any meaningful, open manner; they speak past each other, reserving their true thoughts to themselves and to us, who as readers are granted privileged access to their inner lives.

Each of the central characters endures pain, loneliness, or despair in isolation. The deaf-mute, Singer:

This was the Antonapoulos who was always in his thoughts. This was the friend to whom he wanted to tell things that had come about. For something had happened in this year. He had been left alone in an alien land. Alone. He had opened his eyes and around him there was much he could not understand. He was bewildered.

In “The Song of the Stoic” (from Tales from the Realm of the Queen of Pentacles) Vega writes of the accumulated toll of a hard life:

I grew and went into the world

I learned to know its code

Of spoken and unspoken

And I learned to love the road

I shoulder every burden like

A mule with a heavy pack

Every coin I earn is another

Knot within my back.

Throughout her novel, McCullers also describes the seen and unseen burdens that scars the bodies and souls of her characters. In one scene, Portia, the doctor’s daughter, tries to explain to her father how his son, Willie, lost both feet while incarcerated. During the exchange, we see again the breakdown in and failure of language:

‘They put our Willie and them boys in this here ice-cold room. There were a rope hanging down from the ceiling. They taken their shoes off and tied their bare feets to this rope. Willie and them there boys lay there with their backs on the floor and their feets in the air. And their feets swolled up and they struggle on the floor and holler out. It were ice-cold in the room and their feets froze. Their feets swolled up and they hollered for three nights and three days. And nobody came.’

Doctor Copeland pressed his head with his hands, but still the steady trembling would not stop. ‘I cannot hear what you say.’

‘Then at last they come to get them. They quickly taken Willie and them boys to the sick ward and their legs were all swolled and froze. Gangrene. They sawed off both our Willie’s feet.’

Later, when he is back home, Willie experiences phantom limb pain:

‘I feel like my feets is still hurting. I got this here terrible misery down in my toes. Yet the hurt in my feets is down where my feets should be if they were on my l-l-legs. And not where my feets is now. It a hard thing to understand. My feets hurt me so bad all the time and I don’t know where they is. They never given them back to me. They somewhere more than a hundred m-miles from here.’

In her song “Men in a War” (from days of open Hand) Vega writes not only of phantom limbs but also of a mute trauma:

Men in a war

If they’ve lost a limb

Still feel that limb

As they did before

He lay on a cot

He was drenched in a sweat

He was mute and staring

But feeling the thing

He had not

Walking

One of Suzanne’s most famous songs is “Cracking” (from the album Suzanne Vega and also Close-Up Volume 3). In it, she explores one of the primary themes of her art – being lost in thought, memory and imagination, often while walking:

It’s a one time thing

It just happens

A lot

Walk with me

And we will see

What we have got

Suzanne’s protagonist is lost in reverie:

The sun

Is blinding

Dizzy golden, dancing green

Through the park in the afternoon

Wondering where the hell

I have been

Mick Kelly also wanders in this way:

A good deal of the time they just roamed around the streets – with her pulling Ralph’s wagon and Bubber following along behind. Always she was busy with thoughts and plans. Sometimes she would look up suddenly and they would be way off in some part of town she didn’t even recognize.

The deaf-mute seeks peace in his wandering walks:

Often he went out for the long walks that had occupied him during the months when Antonapoulos was first gone. These walks extended for miles in every direction and covered the whole of the town.

There is a cold sharp chill in “Cracking” and the motif of senses failing:

My heart is broken

It is worn out at the knees

Hearing muffled

Seeing blind

Soon it will hit the Deep Freeze

And something is cracking

I don’t know where

Ice on the sidewalk

Brittle branches

In the air

The deaf-mute also walks through a cold and beautiful solitude, through a soothing landscape of memory:

There was no part of town that Singer did not know. He watched the yellow squares of light reflect from a thousand windows. The winter nights were beautiful. The sky was a cold azure and the stars were very bright.

Solitude (even when among a crowd) is ever-present in Vega’s music. One hears it in “Cracking,” “Tom’s Diner,” “Rosemary,” “Solitude Standing,” and many other songs. Solitude and alienation envelops each of McCullers’ characters as the novel moves to its denouement.

New York City is My Destination

Mick Kelly has taken a job at the Woolworth’s for ten dollars a week, to help her family make ends meet. It is slow death for her and she knows it.

She was going to work in a ten-cent store and she did not want to work there. It was like she had been trapped into something. The job wouldn’t be just for the summer – but for a long time, as long as she could see ahead. Once they were used to the money coming in it would be impossible to do without again. That was the way things were.

Mick wants to write music. She

would bring out her private box from under the bed and sit on the floor to work.

In the big box there were pictures she had painted at the government free art class. She had taken them out of Bill’s room. Also in the box she kept three mystery novels her Dad had given her, a compact, a box of watch parts, a rhinestone necklace, a hammer, and some notebooks. One notebook was marked on the top with red crayon – PRIVATE. KEEP OUT. PRIVATE – and tied with a string.

She had worked on music in this notebook all the winter. She quit studying school lessons at night so she could have more time to spend on music. Mostly she had written just little tunes – songs without any words and without even any bass notes to them. They were very short. But even if the tunes were only half a page long she gave then names and drew here initials underneath them.

In our last glimpse of Mick in the novel one senses that the special, fleeting time between child and young woman has ended. The job is the vampire she knew it would be:

What good was it? That was the question she would like to know. What the hell good was it. All the plans she had made, and the music. When all that came of it was this trap – the store, then home to sleep, and back at the store again…

But now no music was in her mind. That was the funny thing. It was like she was shut out from the inside room. Sometimes a quick little tune would come and go – but she never went into the inside room with music like she used to do.

Mick Kelly disappears from our view; the novel comes to an end. My fear has been that Mick did not pursue her music – she remained trapped, her dreams ground away.

But I think there’s another ending to Mick’s story. Just before Christmas 2015 Suzanne played a show, in New York City, for a neighborhood charity. The show was in Harlem where she grew up.

She sang a song titled “New York City is My Destination.” It is a song written to tell the story of Carson McCullers. As Suzanne/Mick sang the song I could imagine that Mick Kelly had achieved her dreams in music, that she was standing “up on the platform in front of the big crowds of people” as “a great world-famous composer” in New York. This is how I prefer to imagine what became of Mick Kelly.

Sources

The quotes from The Heart is a Lonely Hunter are from the Mariner Books edition, 2000.

“First Day Out” is found in the book The Passionate Eye by Suzanne Vega, Avon Books 1999. This book in general is a good example of the parallels between the work of Vega and McCullers.